This article first appeared on LinkedIn.

“Could we serve more students without incurring additional costs?”

“How can we know if our current expectations of faculty workloads make sense?”

“Can we afford to expand our academic team next semester?”

Whether you’re a department head, CFO, vice provost or academic dean, providing answers to the above questions may not seem straightforward. Yet in times of crisis—and even in periods of relative prosperity—using data to make critical decisions can help institutional leaders to both plan ahead and carefully navigate potential fiscal challenges. Strategic finance encourages colleges to thoughtfully direct resources to programs and activities that reflect their mission, current market realities, and sustainable practices that support student success. It is a data-driven decision-making strategy that requires a better understanding of how financial and human resources are currently used, and how they can be reallocated to better serve students.

As institutions and systems take on the more challenging structural questions around academic efficiency, we’re finding that faculty throughput is a useful metric. Faculty throughput measures the average number of student credit hours (SCH) supported by faculty. Efficiency-related metrics like faculty throughput indicate 1) whether student demand and program capacity are aligned, and 2) where colleges can create real financial savings when taking steps to reduce structural inefficiencies.

Faculty throughput is a comprehensive measure that includes all undergraduate and graduate credit hours, divided by the number of full-time equivalent (FTE) faculty. This metric is helpful in three different ways:

1. Faculty throughput provides information to help right-size colleges’ instructional capacity.

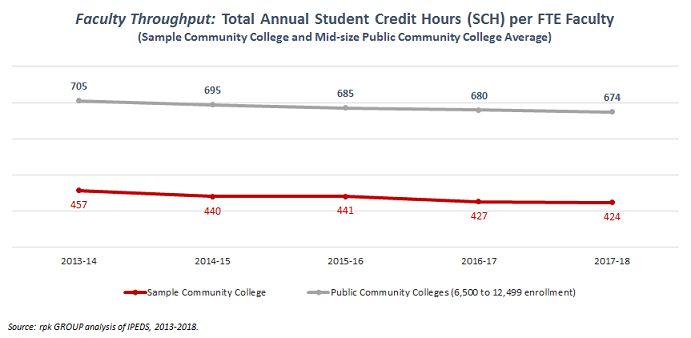

This metric illustrates the balance between student course enrollments and instructional faculty. Throughput metrics are most meaningful when benchmarked against sector and peer group averages to provide context. The figure below shows a sample community college with a faculty throughput equal to 424, which offers little guidance until we see it’s 37% lower than the average mid-size community college.

In this context, the college is actually operating well below potential instructional capacity levels and should be able to serve significantly more students without hiring additional faculty. Of course, some colleges may be operating well above desired capacity. They will need to assess whether faculty workload expectations are too high and additional faculty should be hired to meet student enrollment demand.

2. Trends in faculty throughput are a reliable way of showing whether academic efficiency is moving in the desired direction.

In the example above, faculty throughput has decreased across the sector as course registrations declined more rapidly than faculty rolls. Ideally, this community college would recruit more students or encourage additional course taking among existing students to reverse this trend. But quicker results may be achieved by reducing the number of FTE faculty, and redirecting faculty throughput closer to the sector average.

It’s important to note that reductions in FTE faculty often can be initially achieved by hiring fewer adjunct faculty. Colleges would need to examine the number of course sections offered, and individual section sizes to determine where academic efficiencies can be gained. Deeper structural changes may require that colleges undertake more comprehensive examinations of the academic programs they offer.

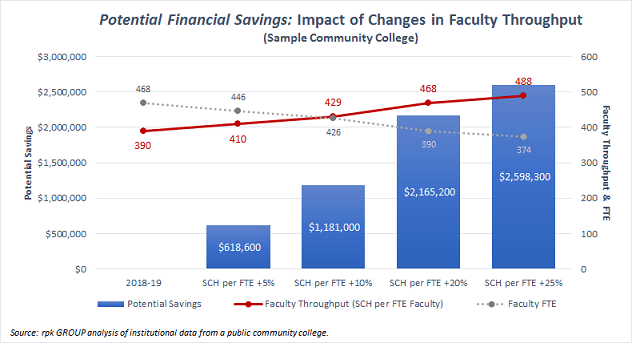

3. Making a course correction to faculty throughput can generate real financial savings for colleges. Repositioning throughput is more than just an academic exercise in moving toward a sector average. At the college shown, increasing faculty throughput by just 5%—from 390 to 410—would generate more than $600,000 in salary savings as efficiency improvements require 22 fewer FTE faculty. A more aggressive approach to increase faculty throughput by 25% (which is still 28% below the sector benchmark average) would save more than $2.5 million in salary expenditures, and reduce the number of required FTE faculty by nearly 100.

The faculty throughput metric serves as a better indicator of workload than the more common college metric showing how many courses a faculty member is teaching, as the ‘course load’ metric doesn’t account for the number of students enrolled. Traditional student-to-faculty ratios do account for student enrollment but are different in that they are used as a metric of class size rather than faculty instructional activity.

Of course, the faculty throughput metric serves as only one view of faculty contribution and must be evaluated in light of other responsibilities for research and service. That balance among teaching, research and service, however, is best obtained when faculty contribution is clearly connected to an assessment of business model sustainability.