By Raven Moody, Senior Analyst and Alisa Cunningham, Specialist.

This article was first published in our monthly rpk GROUP update. Sign up for our newsletter and get strategic finance updates delivered right to your inbox.

The pandemic has ushered in an age of unprecedented insecurity for higher education institutions. Those that survive and prosper will apply data-driven strategies, ensuring that course offerings best reflect mission and market demand. Institutional leaders need to move beyond instincts and guesswork to determine how to best structure courses given increasingly scarce resources. In a nutshell: a course analysis is an essential tool for increasing efficiency while maintaining the quality of instruction. It addresses questions such as:

- Do program requirements and student interest justify the current schedule of course sections?

- Can you increase efficiency by changing the number of sections, class sizes, and fill rates?

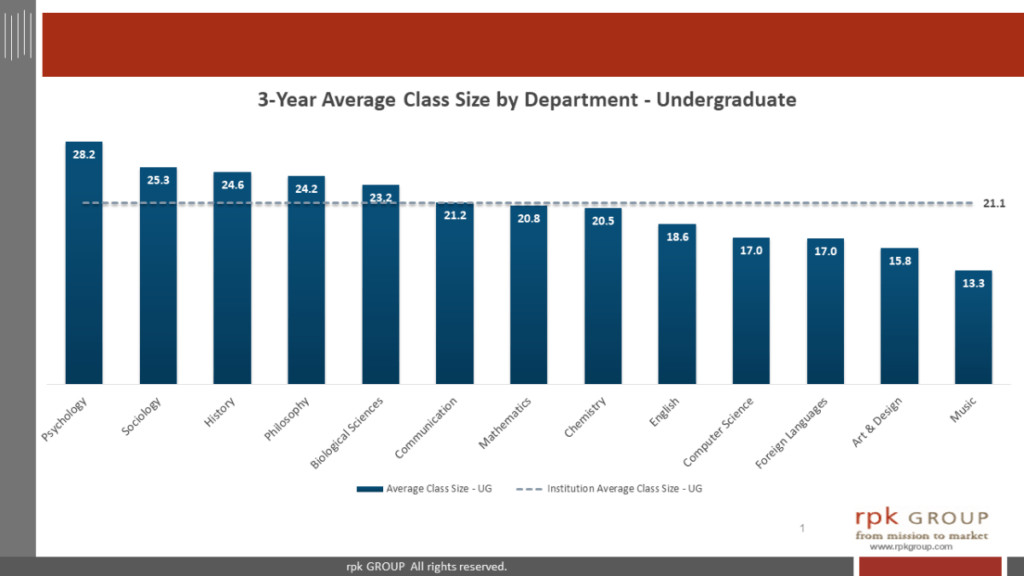

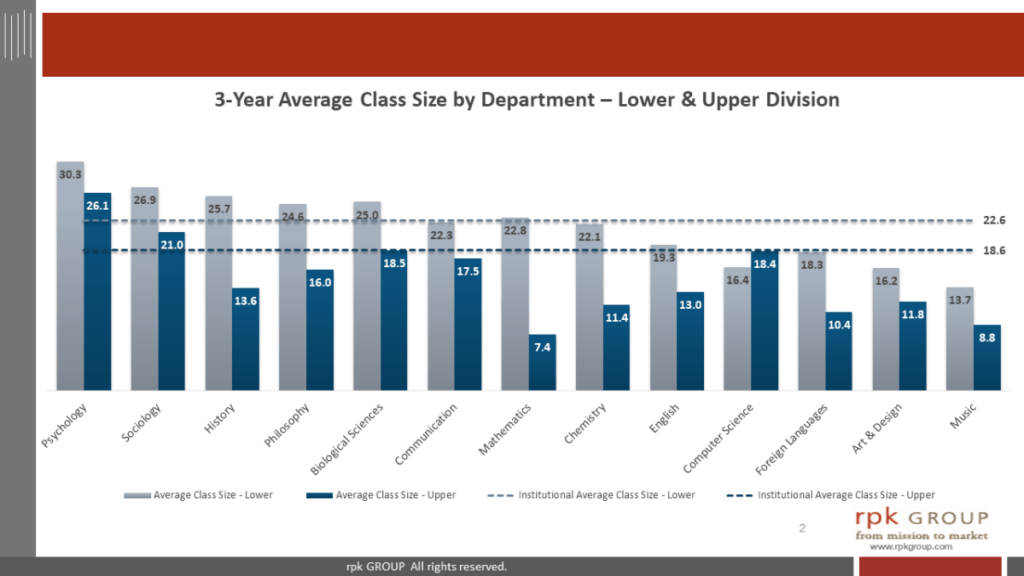

Provosts or deans often initiate a course analysis, but department leaders must embrace the effort. The critical first step is to disaggregate course enrollments. At rpk GROUP, we find that aggregated data often mask meaningful differences within a department, leading to less than ideal decisions.

To illustrate this issue, the following graphs focus on undergraduate courses offered by one client’s math department. Overall, the department’s average class size was close to the institutional average for undergraduate level courses. Digging deeper, however, we found that the aggregated data masked very low student interest in upper-division courses. Specifically, the lower-division courses had an average class size of 23 compared to seven in upper-division courses. This finding was also reflected in average fill rates. Lower-division courses enjoyed relatively high fill rates of 80%, while upper-division courses were filled only 36% on average. While many lower-division courses were fulfilling general education requirements, few students were continuing on to the upper-division courses. The math department needed to recalibrate its course offerings to better reflect student and program needs.

Over time, we’ve used a course analysis to help institutions identify sections with very low enrollment or lower-than-expected class sizes or fill rates. Although courses may occasionally have intentionally low student enrollment, it may also signal areas of low student interest or where the number of sections exceeds demand. Once institutions identify areas of inefficiency, department leaders can dive deeper into the data to determine whether and how to adjust the schedule of course sections. Even with the best data, such discussions and decisions are often painful; without the data, however, the results are far less likely to succeed.